If you have

more than one physical location, in addition to your ecommerce site,

you need a store locator. Slapping all your store addresses on a single

web page and calling it done doesn’t cut it for shoppers or for natural

search performance.

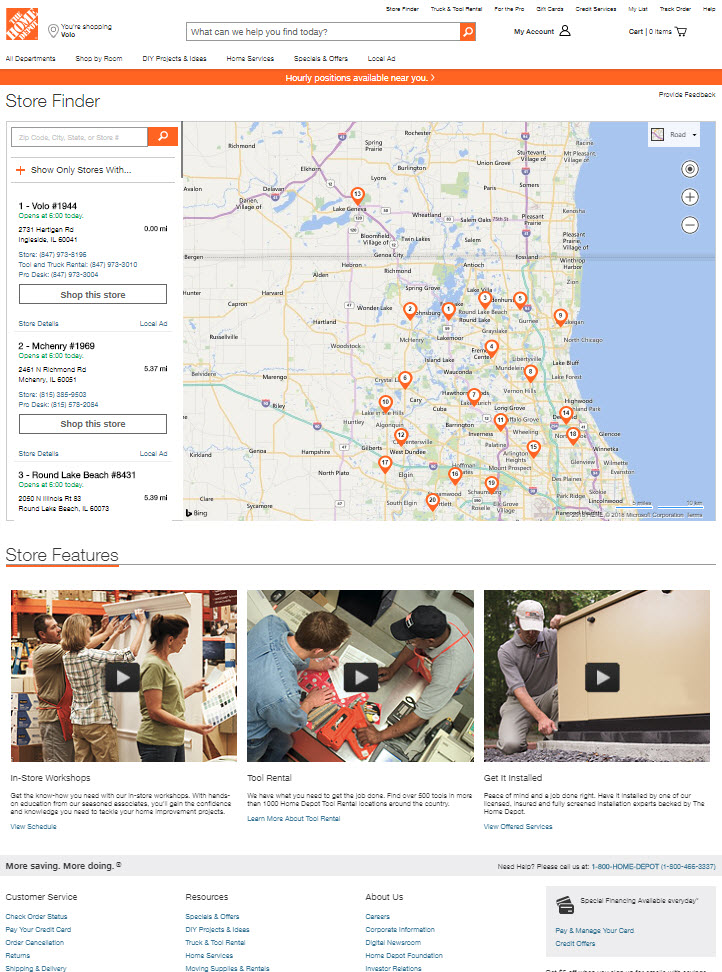

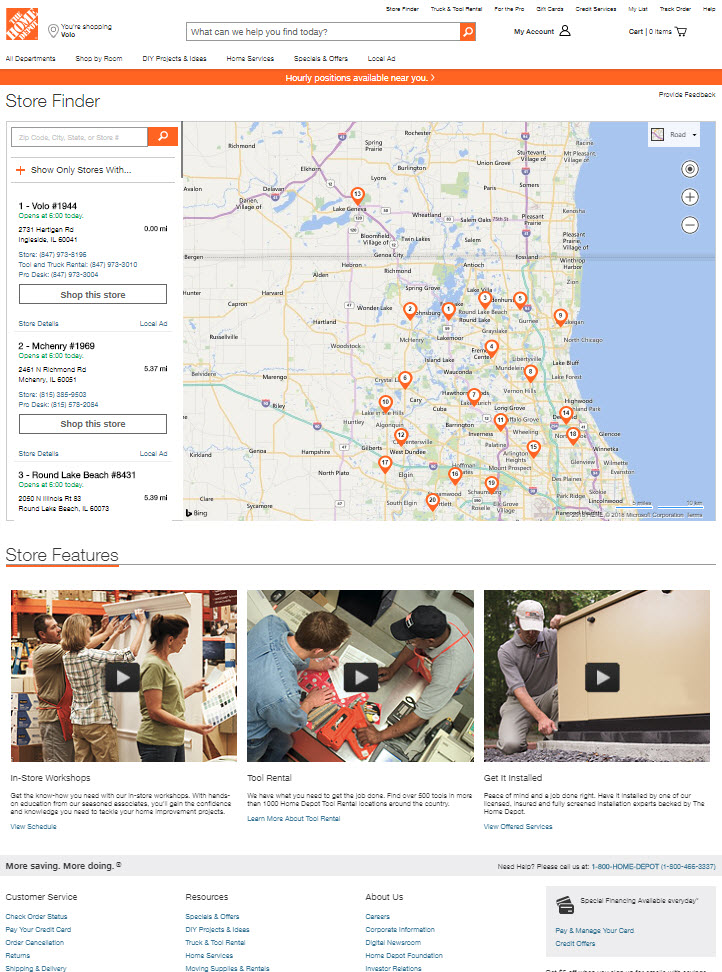

An optimal store locator should be searchable for your customers and also crawlable for the search engines. Shoppers on your site want an experience that targets their location or at least offers them an easy way to select a store, such as a location search box to enter their zip code.

To accommodate crawlers — and to drive local consumers to your stores

instead of your competitors’ — your location finder must have a clear

crawl path to an individual page for every store location.

To accommodate crawlers — and to drive local consumers to your stores

instead of your competitors’ — your location finder must have a clear

crawl path to an individual page for every store location.

That doesn’t mean you have to contract with an expensive local-search vendor if you only have a handful of stores. Use the examples below to create your own. If you have more than 10 stores, though, you may want to consider a more scalable solution that provides an optimal on-site location experience for searching and browsing as well as data distribution to the necessary location players — map providers, yellow page databases, social sites, there are over 300 different entities that deal with location on the internet. You want them all to have the correct location data.

If you have five locations, that’s pretty easy. You need only one location landing page with five links to five separate location pages, one for each store.

If you have 500 locations, the task is harder. Let’s say your stores are located in 32 U.S. states. Your location finder would need to link to 500 individual pages. That’s an overwhelming list for anyone to navigate — yes, shoppers will be navigating it, too.

Instead, create a short journey that takes shoppers and crawlers alike from the location landing page to one that lists the states in which your company has stores. From there, clicking on a state would result in another page that lists the cities in which stores are located, including the store name if a city has multiple locations. Lastly, clicking on the city or store name would take you to the individual store location detail page.

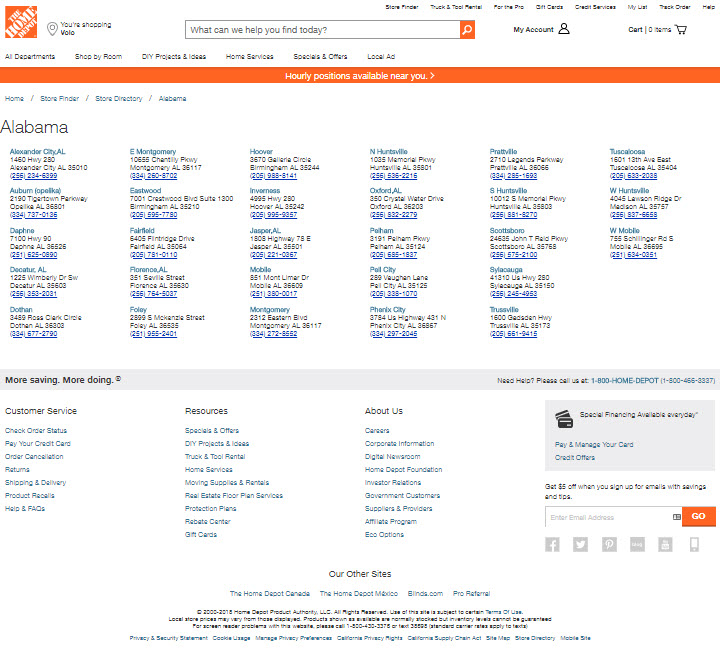

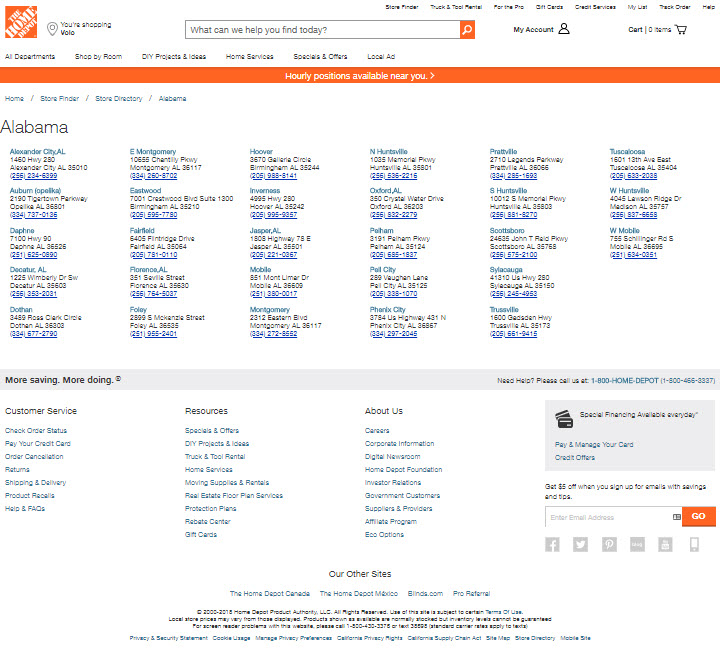

The Home Depot provides an excellent example of this flow from state to city to location detail page. The landing page below lists all of the states in which The Home Depot has a store.

—

—

Clicking on a state takes you to a new page that shows the city in which the store resides, with the associated address and phone number. For cities in which there are two locations, the store name is more precise, such “W Mobile” and “Mobile,” for the two stores in Mobile, Alabama.

—

—

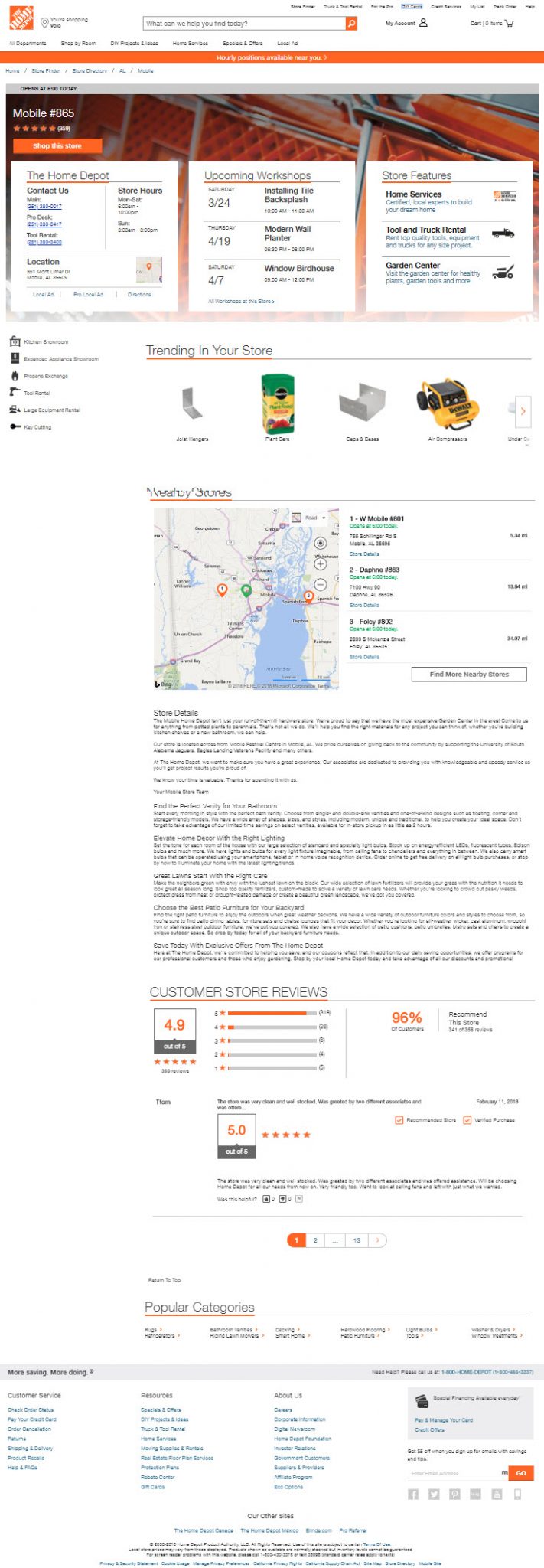

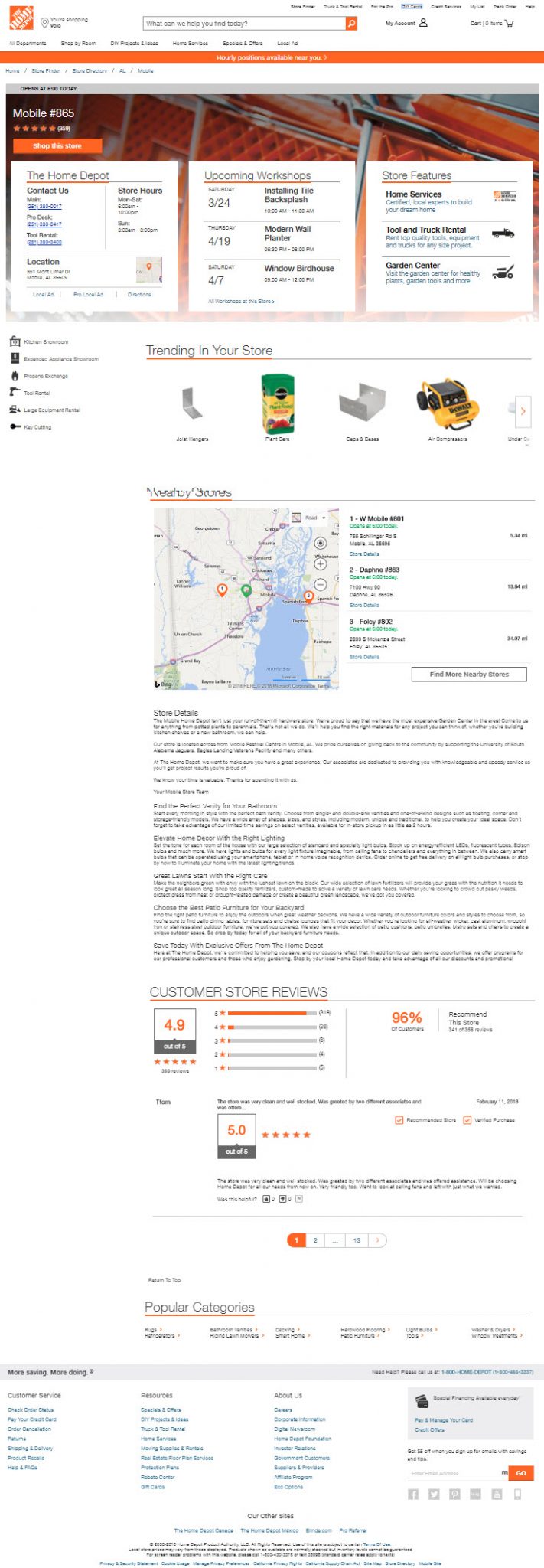

But most importantly for natural search, the experience doesn’t stop there. The Home Depot offers a detailed page for each location, accessible by clicking on the location name from the state page.

These location detail pages contain presumably most everything

shoppers could want when they’re looking for a home improvement store.

This includes a map, address, phone number, and hours of operation.

These location detail pages contain presumably most everything

shoppers could want when they’re looking for a home improvement store.

This includes a map, address, phone number, and hours of operation.

Beyond that, the detail pages contain info on local events, store features, and three short paragraphs of unique, local content that describes each store and its immediate area. The longer portion of the content is boilerplate, as are the popular categories at the bottom. But the reviews are not. They are a good way to bring in user-generated relevance.

If you don’t offer this browse path for search bots to store location detail pages, the only other way to provide access is via an XML sitemap. That may get the detail pages indexed, but it doesn’t give them contextual relevance within your site, and it can’t pass internal link authority. When an XML sitemap is the only way to index location detail pages, your ability to rank in the traditional search results will suffer.

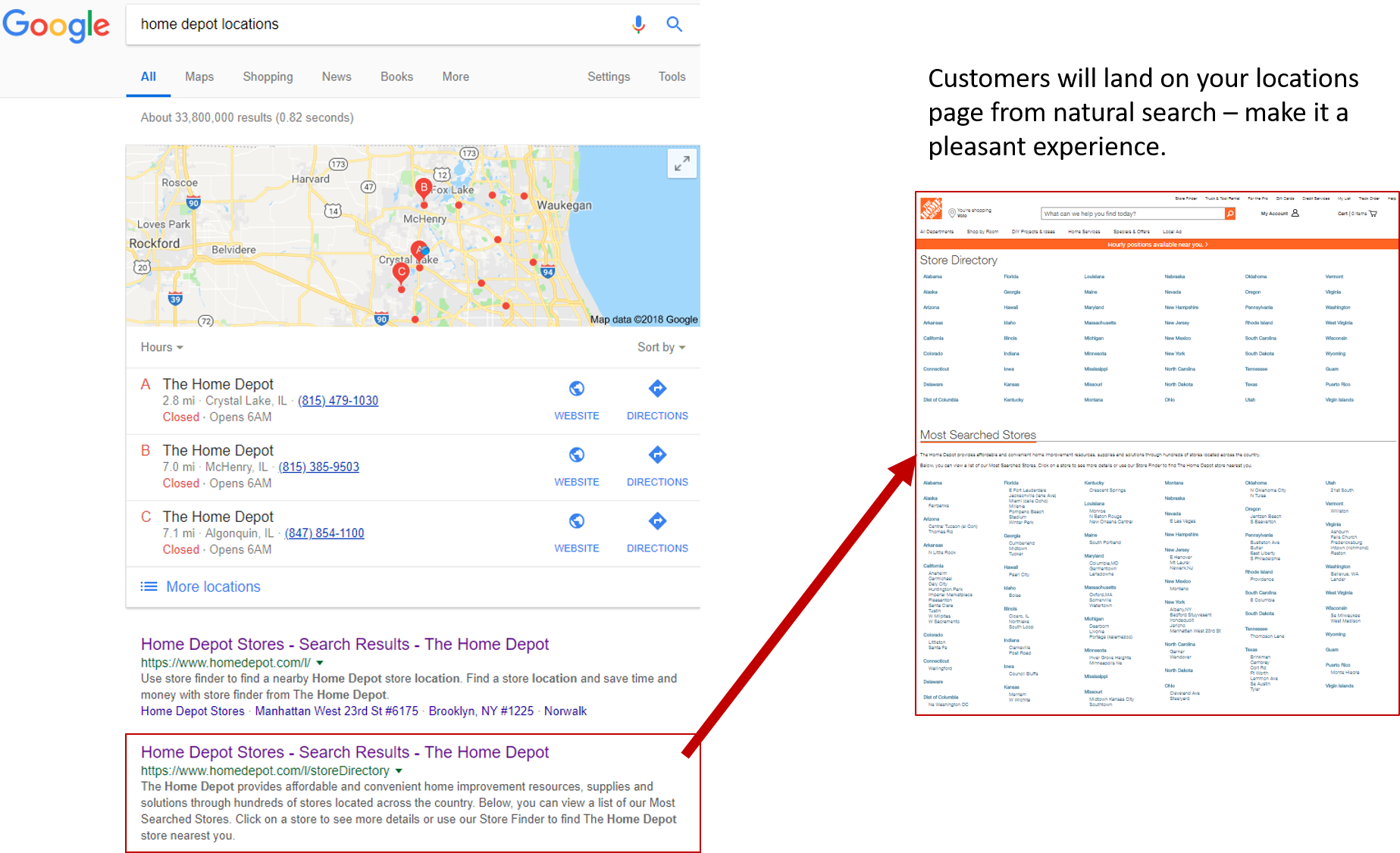

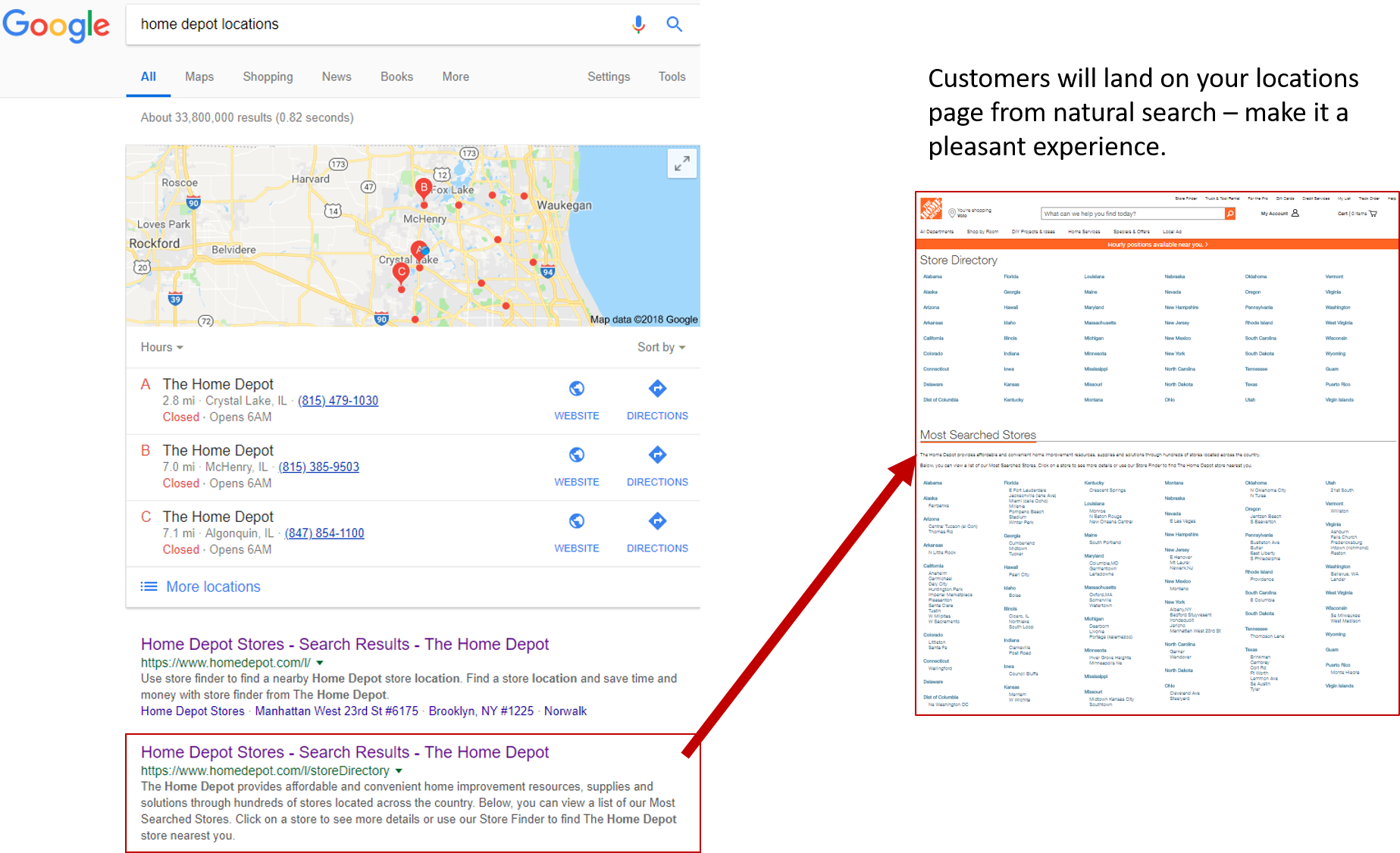

For example, the blander store directory sitemap page ranks for a

search for The Home Depot’s locations, not its intended visual-map page,

which is more user-friendly. The location directory sitemap is better

optimized to win the search, with text that targets the relevant

keywords, headings, and links to each store. In other words, Google

understands the store directory sitemap page better than visual-map

version.

For example, the blander store directory sitemap page ranks for a

search for The Home Depot’s locations, not its intended visual-map page,

which is more user-friendly. The location directory sitemap is better

optimized to win the search, with text that targets the relevant

keywords, headings, and links to each store. In other words, Google

understands the store directory sitemap page better than visual-map

version.

If The Home Depot wants the page with the primary store finder map to rank, it needs to merge the two pages with the visual map at the top (for customers) followed by a directory experience on the same page (for the search engine crawlers).

An optimal store locator should be searchable for your customers and also crawlable for the search engines. Shoppers on your site want an experience that targets their location or at least offers them an easy way to select a store, such as a location search box to enter their zip code.

The Home Depot’s location finder is a typical example.

That doesn’t mean you have to contract with an expensive local-search vendor if you only have a handful of stores. Use the examples below to create your own. If you have more than 10 stores, though, you may want to consider a more scalable solution that provides an optimal on-site location experience for searching and browsing as well as data distribution to the necessary location players — map providers, yellow page databases, social sites, there are over 300 different entities that deal with location on the internet. You want them all to have the correct location data.

Optimal Location Directory

The idea is to provide a crawl path that organizes and provides access to a unique page for every store and to organize your locations into manageable chunks.If you have five locations, that’s pretty easy. You need only one location landing page with five links to five separate location pages, one for each store.

If you have 500 locations, the task is harder. Let’s say your stores are located in 32 U.S. states. Your location finder would need to link to 500 individual pages. That’s an overwhelming list for anyone to navigate — yes, shoppers will be navigating it, too.

Instead, create a short journey that takes shoppers and crawlers alike from the location landing page to one that lists the states in which your company has stores. From there, clicking on a state would result in another page that lists the cities in which stores are located, including the store name if a city has multiple locations. Lastly, clicking on the city or store name would take you to the individual store location detail page.

The Home Depot provides an excellent example of this flow from state to city to location detail page. The landing page below lists all of the states in which The Home Depot has a store.

The Home Depot’s landing page links to every state, city, and location.

Clicking on a state takes you to a new page that shows the city in which the store resides, with the associated address and phone number. For cities in which there are two locations, the store name is more precise, such “W Mobile” and “Mobile,” for the two stores in Mobile, Alabama.

State pages aren’t exciting, but they’re a necessary step in organizing content when you have many locations.

But most importantly for natural search, the experience doesn’t stop there. The Home Depot offers a detailed page for each location, accessible by clicking on the location name from the state page.

Store location detail pages require locally unique content.

Beyond that, the detail pages contain info on local events, store features, and three short paragraphs of unique, local content that describes each store and its immediate area. The longer portion of the content is boilerplate, as are the popular categories at the bottom. But the reviews are not. They are a good way to bring in user-generated relevance.

If you don’t offer this browse path for search bots to store location detail pages, the only other way to provide access is via an XML sitemap. That may get the detail pages indexed, but it doesn’t give them contextual relevance within your site, and it can’t pass internal link authority. When an XML sitemap is the only way to index location detail pages, your ability to rank in the traditional search results will suffer.

Compelling User Experience

Pay attention to the user experience on these detail pages as well. If the page does well in natural search — which gets searchers into the stores — shoppers will be landing on these location pages first. They must have an experience that meets their needs and represents your brand well.

The Home Depot’s location directory, at right, ranks for a Google search for “home depot locations.”

If The Home Depot wants the page with the primary store finder map to rank, it needs to merge the two pages with the visual map at the top (for customers) followed by a directory experience on the same page (for the search engine crawlers).

No comments:

Post a Comment